David Brooks says America needs a moral revival, but it’s really about the role of government.

Tuesday, September 29, 2009 at 06:21PM

Tuesday, September 29, 2009 at 06:21PM David Brooks says the reason ordinary Americans are suffering economically is that they lack the moral fiber of their parents—it's their own fault, and they must redeem themselves morally and culturally:

Centuries ago, historians came up with a classic theory to explain the rise and decline of nations. The theory was that great nations start out tough-minded and energetic. Toughness and energy lead to wealth and power. Wealth and power lead to affluence and luxury. Affluence and luxury lead to decadence, corruption and decline."

. . . .

But in the U.S., affluence did not lead to indulgence and decline.

That's because despite the country's notorious materialism, there has always been a countervailing stream of sound economic values. The early settlers believed in Calvinist restraint. The pioneers volunteered for brutal hardship during their treks out west. Waves of immigrant parents worked hard and practiced self-denial so their children could succeed. Government was limited and did not protect people from the consequences of their actions, thus enforcing discipline and restraint."

. . . .

Over the past few years, however, there clearly has been an erosion in the country's financial values. . . .

. . . [I]n the three decades between 1950 and 1980, personal consumption was remarkably stable, amounting to about 62 percent of G.D.P. In the next three decades, it shot upward, reaching 70 percent of G.D.P. in 2008.

During this period, debt exploded. In 1960, Americans' personal debt amounted to about 55 percent of national income. By 2007, Americans' personal debt had surged to 133 percent of national income.

Over the past few months, those debt levels have begun to come down. But that doesn't mean we've re-established standards of personal restraint. We've simply shifted from private debt to public debt. . . .

. . . . [T]hese numbers are the outward sign of a values shift. If there is to be a correction, it will require a moral and cultural movement."

There is nothing to the "Calvinist restraint" myth.

Brooks gives no evidence of any change in financially-relevant character or morality in recent decades. To make that case, he should at least argue that the parents and grandparents of today's citizens would make different decisions under today's circumstances, or that they would make more profligate decisions than their ancestors if transported back in time to those circumstances. For example, newly unemployed fathers in today's Great Recession often max out their credit cards to try to maintain a standard of living. That didn't happen in the Great Depression, but was it because of character differences or because there was no access to credit then? Would a typical young father transported from the 1930s to today not borrow to keep his family fed and housed?

Brooks tells us that the American living standards surpassed those in Europe as early as 1740 and continued to grow rapidly because Americans "believed in Calvinist restraint." Really? Free land, abundant natural resources, open immigration policies, rapidly growing population, relative isolation from frequent European wars, use of slavery, and being athwart important trade routes had nothing to do with economic growth in America? C'mon. And whose "restraint" is he talking about? Could he possibly mean that what uber-Calvinists Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller were exercising was "restraint."

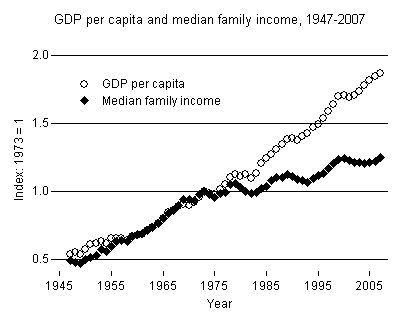

Brooks seems to mean that it's ordinary citizens that must exercise Calvinist restraint in order to prosper, and when they don't, their incomes suffer. Actually, that's the only thing he could mean because incomes have stagnated and declined only for the working class and middle class. Upper economic classes have had their incomes increase faster than before this alleged moral decline suddenly overwhelmed the nation--in about 1973 according to the following charts from here, here, and here.

Wealth is highly concentrated among elites and power even more so, and always has been. How is it that the moral decline of ordinary citizens causes the wealthy and powerful to go soft and stop exercising Calvinist restraint? If moral decline is truly the problem, isn't it the wealthy and powerful, instead of the masses, that should be packed off to re-education camps? These are the people who have been making the rules of the economic game for the last three decades and are its most influential players. For example, ultralow interest rates and other policies that have discouraged saving were put into place not by ordinary consumers who turned into spendthrifts almost overnight but by elites who want the masses to spend as much as possible. So whose values need to change? And who would be doing the re-educating, Brooks' conservative friends of high Calvinist morality who gained ever-increasing control over economic policies in the last 30 years and kept making things worse?

Wealth is highly concentrated among elites and power even more so, and always has been. How is it that the moral decline of ordinary citizens causes the wealthy and powerful to go soft and stop exercising Calvinist restraint? If moral decline is truly the problem, isn't it the wealthy and powerful, instead of the masses, that should be packed off to re-education camps? These are the people who have been making the rules of the economic game for the last three decades and are its most influential players. For example, ultralow interest rates and other policies that have discouraged saving were put into place not by ordinary consumers who turned into spendthrifts almost overnight but by elites who want the masses to spend as much as possible. So whose values need to change? And who would be doing the re-educating, Brooks' conservative friends of high Calvinist morality who gained ever-increasing control over economic policies in the last 30 years and kept making things worse?

The real issue is whether government can and should adjust the rules to make capitalism work or whether we should blame the victims and let economic powers run free without checks and balances.

The idea that people are poor because they are sinners, or are simply pre-destined to be inferior, resurrects (as historian and sociologist Brooks surely knows) the social Darwinist side of the political argument with the Progressive Movement a century ago. Please forgive the oversimplification as I try to summarize in two paragraphs Robert H. Nelson's fascinating and extensively researched book Reaching for Heaven on Earth—The Theological Meaning of Economics.

In the late 1800s, the ideas that a "social gospel" commanded humans to strive for heaven on earth and that scientific knowledge enabled selfless government technocrats to facilitate that by channeling the animal spirits and dark impulses of powerful economic players powered the Progressive Movement. Progressives drew on Aristotle, St. Thomas Aquinas, the traditions of the Roman Catholic Church that all men are equal and all can be saved by their lifetime behavior, the optimism that Isaac Newton's discovery of important physical laws could be extended to all fields of inquiry including what came to be called the social sciences, and the writings of John Locke, Adam Smith, Jeremy Bentham, et al. And, of course, they recruited every other possible argument for their ideas about the proper role of government.

Arrayed against them were protestant ideas that this world is irredeemably sinful, that only a few "elect" will go to heaven, and that our earthly deeds cannot influence God's decision in that regard. Those on this side of the argument were influenced by the ideas of Plato, St. Augustine, Martin Luther, John Calvin, Jean Jacques Rousseau, Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, Herbert Spencer, Sigmund Freud, et al. This "social Darwinism" of Herbert Spencer was actually in play before Darwin wrote about the survival of the fittest in the evolution of species. In this view, for government to "interfere" by tipping the scale or changing the rules against the elect and in favor of the damned was a sinful interference with God's ordained natural order.

In this context it seems to me that Brooks has defined the problem and the solution as requiring that the masses of men must repent and change their essential morals and culture and that unless they do, nothing can—or should—be done. The problem has not been caused by improvident government policies, and government should not try to change outcomes by some technocratic policy adjustment, he's saying.

My view is closer to the progressive side, although it has from time to time clearly overestimated its ability to understand economic science and optimize the workings of government. Government has an essential and unavoidable role in making and enforcing the rules of the economic game. It need not (and should not) be the central planner or the owner of all capital, but all games must have rules and there is no other entity that can make and enforce them. In an NFL metaphor, government is the "competition committee" that periodically adjusts the rules for the protection of players and maximization of the fan base and revenues. None of the rules, and none of the rule changes, can be entirely neutral. For example, rule changes that protect quarterbacks and wide receivers increase the advantage of teams that are staffed to pass, and rule changes that protect defensive linemen from low blocks may make them stronger against running plays. A game with no rules, or "rules" made up on the fly by the players, is doomed to failure.

I'll tell you who's gone soft, and it's not the American people. Usually hard-headed David Brooks has become a squishy romantic (unless he's a cold-blooded acolyte of Herbert Spencer, which seems more likely).

Skeptic

Skeptic

Paul Krugman sees the finger prints of Ronald Reagan, Irving Kristol, et al. instead of moral decay. Andrew Leonard characterizes it as The Decline and Fall of David Brooks.

Skeptic

Skeptic

Jason Burwen's comment on Mark Thoma's blog presents data that it's upper income strata that saved less in the 1990s:

Skeptic

Skeptic

Brooks confirms in today's column that he is thinking in terms of the great philosophical divide of 100 years ago as we are "about to have a big debate on the role of government." He says we should be following David Hume (Calvinist) because that will unleash innovation, but regrets we're probably going to follow Jeremy Bentham (progressive) in healthcare and climate change legislation because that's what entrenched interests want.

Skeptic

Skeptic