Avenging lobsters bring Bernie Madoff to justice.

Thursday, March 26, 2009 at 04:46PM

Thursday, March 26, 2009 at 04:46PM Woody Allen's hilarious story is here.

Thursday, March 26, 2009 at 04:46PM

Thursday, March 26, 2009 at 04:46PM Woody Allen's hilarious story is here.

Thursday, March 26, 2009 at 09:51AM

Thursday, March 26, 2009 at 09:51AM Nicholas Kristof reviews research on 82,000 predictions by 284 "experts" to find what characteristics are associated with success.

Indeed, the only consistent predictor was fame — and it was an inverse relationship. The more famous experts did worse than unknown ones. That had to do with a fault in the media. Talent bookers for television shows and reporters tended to call up experts who provided strong, coherent points of view, who saw things in blacks and whites. People who shouted — like, yes, Jim Cramer!

Mr. Tetlock called experts such as these the "hedgehogs," after a famous distinction by the late Sir Isaiah Berlin (my favorite philosopher) between hedgehogs and foxes. Hedgehogs tend to have a focused worldview, an ideological leaning, strong convictions; foxes are more cautious, more centrist, more likely to adjust their views, more pragmatic, more prone to self-doubt, more inclined to see complexity and nuance. And it turns out that while foxes don't give great sound-bites, they are far more likely to get things right.

This was the distinction that mattered most among the forecasters, not whether they had expertise. Over all, the foxes did significantly better, both in areas they knew well and in areas they didn't.

Kristoff also observes that pundits are seldom held accountable for being wrong. To the contrary, they get more media attention because their fame is increasing. This provides substance to the ideas that "there is no bad publicity" and "it's better to be wrong than to be irrelevant." It also suggests that what rises to the top even in "serious" media may be froth and not cream. I doubt this means I can get rich betting against famous hedgehogs like, say, Jim Cramer, but it does reinforce my preference for having judgments that affect my life made by foxes instead of hedgehogs. Barack Obama instead of George W. Bush, for example.

Tuesday, March 24, 2009 at 12:32PM

Tuesday, March 24, 2009 at 12:32PM Several commentators think the Public-Private Investment Partnership plan announced yesterday to boost the prices of toxic assets and take them off the hands of troubled banks will do some good but not enough. Brad DeLong suggests the reason:

Why isn’t the administration doing the entire job? My guess is that the Obama administration wants to avoid anything that requires legislative action. The legislative tacticians appear to think that after last week’s furor over the A.I.G. bonuses, doing more would require a congressional coalition that is not there yet. The Geithner plan is one the administration can do on authority it already has.

Friday, March 20, 2009 at 02:43PM

Friday, March 20, 2009 at 02:43PM Adam Smith would have been appalled but not surprised by the AIG executive bonus debacle. He understood that the managers of a joint stock company do not have the same interests as the owners and are not likely to watch over other people's money the same way they do their own.

The directors of such companies, however, being the managers rather of other people's money than of their own, it cannot well be expected that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners in a private copartnery [sic] frequently watch over their own. Like the stewards of a rich man, they are apt to consider attention to small matters as not for their master's honour, and very easily give themselves a dispensation from having it. Negligence and profusion, therefore, must always prevail, more or less, in the management of the affairs of such a company.

Sunday, March 15, 2009 at 11:48AM

Sunday, March 15, 2009 at 11:48AM I have been such a strong critic of the dominant neoclassical school of economics and free market fundamentalism, that I could perhaps be misunderstood as wanting to replace it with a better paradigm, or even to keep all discussion of economics out of public policy discourse. Not so. I agree with Dani Rodrik's essay with this title that we need more to reform the economists than the economics.

The fault lies not with economics, but with economists. The problem is that economists (and those who listen to them) became over-confident in their preferred models of the moment: markets are efficient, financial innovation transfers risk to those best able to bear it, self-regulation works best, and government intervention is ineffective and harmful.

They forgot that there were many other models that led in radically different directions. Hubris creates blind spots. If anything needs fixing, it is the sociology of the profession. The textbooks at least those used in advanced courses - are fine.

Non-economists tend to think of economics as a discipline that idolizes markets and a narrow concept of (allocative) efficiency. If the only economics course you take is the typical introductory survey, or if you are a journalist asking an economist for a quick opinion on a policy issue, that is indeed what you will encounter. But take a few more economics courses, or spend some time in advanced seminar rooms, and you will get a different picture.

Well, that's a pretty big problem because millions of ordinary citizens and policy makers have been indoctrinated with "the typical introductory survey," and never get to the advanced seminar rooms. And then he goes on to describe the damage done by advanced training in macroeconomics, but regrettably does not call out academic economists for not reforming the way they teach survey courses and advanced macroeconomics.

. . . .

Macroeconomics may be the only applied field within economics in which more training puts greater distance between the specialist and the real world, owing to its reliance on highly unrealistic models that sacrifice relevance to technical rigor. Sadly, in view of today's needs, macroeconomists have made little progress on policy since John Maynard Keynes explained how economies could get stuck in unemployment due to deficient aggregate demand. Some, like Brad DeLong and Paul Krugman, would say that the field has actually regressed.

Economics is really a toolkit with multiple models - each a different, stylized representation of some aspect of reality. One's skill as an economist depends on the ability to pick and choose the right model for the situation.

Economics' richness has not been reflected in public debate because economists have taken far too much license. Instead of presenting menus of options and listing the relevant trade-offs - which is what economics is about - economists have too often conveyed their own social and political preferences. Instead of being analysts, they have been ideologues, favoring one set of social arrangements over others.

Exactly. Every economic model necessarily starts with simplifying assumptions. Instead of always starting with assumptions that seem most likely to be true about the bit of reality being studied--and actually testing assumptions against reality--too many economists seem to use only the assumptions that for philosophical and political reasons they would like to see in some utopian world.

One of the problems may be that economics is not a "profession" like law, medicine, engineering, accounting, etc. "Professionals" are generally held accountable for giving bad advice or putting their own interests ahead of the clients', but it would be pretty hard to sue an economist on either ground. The Harvard Business School and other graduate schools of management are reconsidering whether they have erred by not making management more of a profession, as reported in the New York Times today.

For all of the emphasis on analytical rigor in business schools today, another major recommendation of the foundations' reports from the 1950s — that business become a true profession, with a code of conduct and an ideology about its role in society — got far less traction, said Rakesh Khurana, a professor at Harvard Business School and author of "From Higher Aims to Hired Hands," a historical analysis of business education.

Business schools, he said, never really taught their students that, like doctors and lawyers, they were part of a profession. And in the 1970s, he said, the idea took hold that a company's stock price was the primary barometer of success, which changed the schools' concept of proper management techniques.

Instead of being viewed as long-term economic stewards, he said, managers came to be seen as mainly as the agents of the owners — the shareholders — and responsible for maximizing shareholder wealth.

"A kind of market fundamentalism took hold in business education," Professor Khurana said. "The new logic of shareholder primacy absolved management of any responsibility for anything other than financial results."

Thursday, March 12, 2009 at 12:12PM

Thursday, March 12, 2009 at 12:12PM The Federal Reserve Board today released its quarterly Z.1 report on the economy. Net worth of American households and non-profit organizations shrank to $51.5 trillion. This is down $12.9 trillion (20%) from the peak of $64.4 trillion in the second quarter of 2007 and is below the $51.9 trillion figure for 2004. Easy come, easy go.

Skeptic

Skeptic

In the first quarter of 2009, net worth shrank to $50.4 trillion, according to the Feds Z.1 report released today. Meanwhile, the December 31, 2008 value was revised upward from $51.5 trillion to $51.7 trillion.

Skeptic

Skeptic

The report for the second quarter of 2009 is out today. Q1 net worth was revised upward to $51.1 tln, and Q2 is reported at $53.1 tln. The $2 tln increase was entirely in financial assets, and about 80% of the increase was in the market value of equities. Oddly, there were also major upward revisions in the 2008Q4 numbers ($51.5 tln to $52.9 tln) and the 2004Q4 numbers ($51.9 tln to $52.5 tln). Hmmm.

Wednesday, March 11, 2009 at 02:59PM

Wednesday, March 11, 2009 at 02:59PM The beneficiary of a credit default swap on a company's debt may get a huge payoff from the issuer of the CDS if the covered company defaults on its debt. It is reported that CDS holders of Lyondellbasell are trying to force it into bankruptcy for just that reason. The value of CDSs outstanding on the debt of a big company like GM can be much larger that the face amount of the debt because one does not have to own the debt to enter into a CDS. AIG was a big issuer of CDSs, and it would not be shocking to learn that AIG (and, therefore, US taxpayers) would be one of the biggest losers if GM is not able to avoid bankruptcy.

Wednesday, March 11, 2009 at 10:54AM

Wednesday, March 11, 2009 at 10:54AM President Obama is operating in a way that deprives Congressional Republicans of their best political weapon and preferred and perfected mode of operation—the politics of personal destruction. Because he is nice to them, eloquent in public, hard-working, optimistic, and apparently competent, their attempts to portray him as a villain backfire. Obama has said he admires the transformations of the Reagan administration, and it seems he's emulating a style that coated Reagan with Teflon and was so instrumental in his effectiveness.

So long as the Teflon holds up, Congressional Republicans have nothing left but strategies that are less effective for them. They are particularly weak on their understanding of and interest in new policies that voters find credible, and their legacy policies are very unpopular. During the 2008 campaign, Republican leaders were saying the GOP brand was broken, but a year ago polls showed that the public hated GOP policies more than their brand. Since Obama has forced the GOP to park the big attack artillery, they are trying to advance behind a barrage of angry and confused mumbling.

Not only has the GOP not had a new policy idea since Newt Gingrich left Congress, but its base is being fractured by internal dissention as they attempt to agree on policies to get beyond "tax cuts, deregulation, and every man for himself personal responsibility." They have evangelicals who are populists and environmentalists and believe in community and helping the needy. They have business leaders who want the federal government to step in and save them. They have governors who have serious budget problems and a sense of responsibility. They have visionaries pointing out that the GOP is doomed demographically if it cannot recruit millions of minorities. And, increasingly, they have insiders and conservative thought leaders who are saying, "It didn't work, and it won't work now; we have to do something different." It appears they are presently the party of "No" precisely because that is the only thing they can agree on. That depresses David Brooks and entertains me.

It seems the national GOP devotes 100% of its thinking to crafting talking points that sound policy-like instead of figuring out how to solve real government-size problems as perceived by voters. Obviously, every party and every politician has to think about the next election, but not thinking at all beyond that is irresponsible and (if there is a God) self-defeating.

Voters are starting to hold Congressional Republicans accountable and will do so even more as the economy sinks deeper and puts more Independents out of work and Independents realize their 401(k)s are not going to recover soon. In swing districts, I think GOP candidates railing against "government deficits that burden future generations" will not resonate as much as Democratic calls for dramatic government actions to fix the economy now. But, the future lies ahead, and Obama and the Dems could easily blow their lead.

Skeptic

Skeptic

Illustrative of the internal dissention is this "conservative's lament" in Newsweek by David Frum, lifelong conservative Republican and former speech writer for Bush 43, now at the American Enterprise Institute.

Tuesday, March 10, 2009 at 05:08PM

Tuesday, March 10, 2009 at 05:08PM Since Bob Herbert wrote about Reviving the Dream today, this is a good time to put up the problem-defining graphs from a longer analysis I haven't finished.

The American middle class and working class are essentially the more than 90 million non-supervisory "production workers" who constitute 84% of non-government, non-farm employment. For 26 years, from 1947 to January 1973, their average hourly pre-tax earnings, adjusted for inflation using current methods, grew robustly and steadily at an average annual "real" rate of about 2.2%. At that rate, average purchasing power would double in 33 years. Parents expected their children to have more prosperous lives than their own, and it was happening. It was the Golden Age of the Middle Class. Then, suddenly and permanently, it ended in February 1973.

The proximate cause of the sudden change is obvious. By definition, all of these "production workers" are "employed," and the BLS hourly earnings statistics are gathered from payroll records. Before 1973, employers as a group were giving their existing workforces average annual pay increases that exceeded the inflation rate by 2.2 percentage points. After 1972, they handed out increases that on average only just kept even with inflation.

Meanwhile, the larger economy measured by real GDP per employee had a stagnant decade from 1973 to 1983. But then it took off and averaged 1.14% annual average growth for 25 years. That is modest growth compared to the 2.69% average from 1947 to 1973, but since 5/6 of American workers got a zero share of the post-1983 growth, those who did —presumably management and the owners of capital—did quite nicely.

So, here's the problem in a nutshell. Average real earnings of the 5/6 of Americans who are production workers cannot go up—and the American Dream cannot be revived—unless employers consistently grant annual wage/salary increases that on average exceed the inflation rate. What changes would motivate and enable large, trend-setting employers to return to giving average annual wage increases—for their existing workforces—that exceed inflation by 1% or 2%?

Skeptic

Skeptic

Why February 1973 and not some other date? Some facts and conjectures: The inflation rate spiked to 12% in 1974 (and later to 15% in 1980), and there was a recession lasting until 1975. Link. The 1973-74 bear market began in February 1973; from a high in January, the value of the S&P 500 declined by more than half over the next 21 months. Link. The trailing 12-months P/E ratio of the S&P 500, which had been close to 17-18 since 1958 slumped to 7-11 for about a decade. Link. Presumably, there was a perception that the quality of corporate earnings was poor because they were being largely eaten by inflation. I recall great pressures, including from leveraged hostile take-overs, to cut costs, boost near-term earnings, and "create shareholder value." Perhaps that's enough to account for the real hourly earnings decline from 1973 until the 1983 end of a deep recession. But why did real hourly earnings continue to stagnate from 1983 to 1997? And from 2002 to 2009?

Skeptic

Skeptic

David Kamp says that the idea of economic progress for the middle class is outmoded and we should get used to the idea of continuity.

And what about the outmoded proposition that each successive generation in the United States must live better than the one that preceded it? While this idea is still crucial to families struggling in poverty and to immigrants who’ve arrived here in search of a better life than that they left behind, it’s no longer applicable to an American middle class that lives more comfortably than any version that came before it. (Was this not one of the cautionary messages of the most thoughtful movie of 2008, wall-e?) I’m no champion of downward mobility, but the time has come to consider the idea of simple continuity: the perpetuation of a contented, sustainable middle-class way of life, where the standard of living remains happily constant from one generation to the next.

By what measure does the American middle class live more comfortably than the 1972 version? Mr. Kamp seems not to be familiar with the BLS data.

If we're considering continuity for the American middle class, are we going to consider with equal openness economic continuity for the American upper class and working class, and the masses of Chinese, Indians, and Africans? How did the American middle class earn the right and duty to give up its dreams to pay for everybody else's economic advancement?

Skeptic

Skeptic

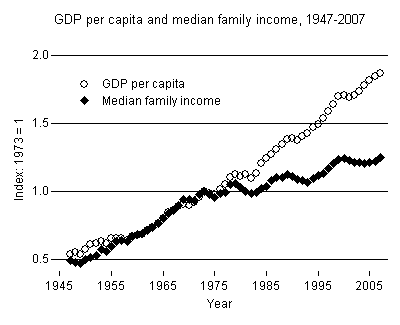

Lane Kenworthy has graphs of real median family income and real GDP per capita here.

Median family income continued to rise after 1972 but at a much slower rate than before. Presumably, family incomes continued to grow as hourly earnings declined and stagnated because increasingly families had two earners and/or worked longer hours. Note also that Kenworthy reports median incomes, not average incomes.

Skeptic

Skeptic

According to a staff report to Obama's Middle Class Task Force:

[T[he President and Vice President recognize that helping families make it through these hard times is just one part of their agenda for lifting up the middle class. They also are acutely aware of the disconnect between growth and middle-class incomes that persisted even in good times. They know, therefore, that an economic recovery is necessary, but not wholly sufficient to lift the fortunes of the middle class and to correct the economic imbalances that held them back in recent years.

I've seen no evidence that the Middle Class Task Force has seized upon real average hourly earnings as a key focus of its attention.

Skeptic

Skeptic

This study by MIT professor David Autor, using household survey data that include all types of employment, shows that real hourly incomes of lower wage workers (below about the 60th percentile) declined from 1973-89, while the real hourly incomes of higher wage workers increased. From 1989 to 2005, wages at all income levels increased, with those at the top and bottom doing better than those in the middle.

Skeptic

Skeptic

Gjerstad and Smith argue that the Consumer Price Index has substantially understated inflation since 1999.

In 1983, the Bureau of Labor Statistics began to use rental equivalence for homeowner-occupied units instead of direct home-ownership costs. Between 1983 and 1996, the price-to-rental ratio increased from 19.0 to 20.2, so the change had little effect on measured inflation: The CPI underestimated inflation by about 0.1 percentage point per year during this period. Between 1999 and 2006, the price-to-rent ratio shot up from 20.8 to 32.3.

With home price increases out of the CPI and the price-to-rent ratio rapidly increasing, an important component of inflation remained outside the index. In 2004 alone, the price-rent ratio increased 12.3%. Inflation for that year was underestimated by 2.9 percentage points (since "owners' equivalent rent" is about 23% of the CPI). If home-ownership costs were included in the CPI, inflation would have been 6.2% instead of 3.3%.

To the extent that's right, inflation-adjusted earnings in this period are overstated and are probably still well below the January 1973 level.

Skeptic

Skeptic

Why do real earnings seem to be rising as the current recession takes hold, and what's the outlook? First, nominal earnings rates are very sticky and tend to keep rising even in recessions because employers fear creating bad morale by reducing nominal wages, or even freezing them. Notice in this article that some employers are giving unpaid furlows instead of reducing wage rates.

Second, as employers cut payrolls by reducing head counts, they tend to lay off lower-paid workers first in order to keep their best workers and managers in place for the expected upturn. This causes the average earnings to increase.

Third, in a recession, we stop having inflation and start having deflation in prices. Thus, the change in CPI, which is used to adjust nominal earnings to real earnings, makes real earnings increase even if nominal earnings are flat or even declining.

Federal Express announced across the board wage and salary cuts in mid-December. The Washington Post article linked above reports that hourly earnings rates are now being reduced elsewhere, especially in staffing agency rates. The outlook is for a slow recovery of nominal earnings, according to the WaPo piece:

Experts fear that wages will not keep up. Once the recession ends, economists expect, the recovery will be long and slow, with sluggish job creation. Without a tight labor market, employers won't have to compete as much for talent and workers will have less leverage to push for higher pay, experts say.

"Once you knock down wage growth, it will take a substantial change in unemployment to move it again," said Lawrence Mishel, president of the Economic Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank in Washington. "The recovery is going to be weak. I think as wage growth subsides, it is going to subside for many years."

Update 17 May 2009: The New York Times reports that the proportion of companies that have implemented salary reductions increased from 8% in February to 21% by the end of April, based on data supplied by compensation consultant Watson Wyatt.

Skeptic

Skeptic

Paul Krugman agrees there seems to be a general decline in wages explains why that's bad for the economy here.

Skeptic

Skeptic

Will Wilkinson of the Cato Institute says in 28 pages that the middle class should stop whining about their stagnant and declining incomes and realize that money can't buy happiness. James Kwak pushes back here.

Skeptic

Skeptic

Inflation-adjusted average weekly earnings shows a similar pattern, with August 2009 on the rise but still below the 1960s and 1970s, according to this LAT story.

Skeptic

Skeptic

Here's a source that says HP employees haven't had a wage increase in 8 years because HP wants to shed domestic employees and offshore their work.

Skeptic

Skeptic

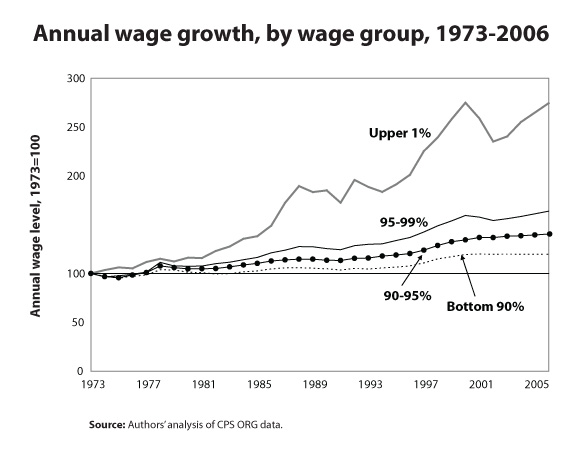

The first graph in the initial post shows that real hourly earnings for production workers--i.e., the ~5/6 of the working population who are not bosses--have not increased at all since 1973. Here is another graph from Economic Policy Institute that shows there has been only a tiny gain in the average wage level of the bottom 90 percent of all income earners, and almost all of those gains occurred between about 1996 and about 2000 during the dot-com era.

As the following graph from the same EPI post shows, instead of the bottom 90% of income earners getting 90% of the income gains from 1973 to 2006, they got only 15.9%, while the top 1% got 55.6% of the income gains, and 62% of that share went to the top 0.1%.

In an earlier post, I showed how US real median family income grew steadily from 1947 to 1973 at a compound average annual rate of 3.19%, yielding a doubling time of 23 years. From 1973 to 2006, the rate of increase for the bottom 90% was 0.50%, yielding a doubling time of 144 years. In effect, if not intentionally(?), the economy has developed in ways that steer 100% of the gains to elites. What caused this sea change? Disco perhaps? Resurgence of competition from abroad? Federal government policy changes? Other things? The fundamental question is whether it is appropriate for a "government of the people, by the people, for the people" to set rules for a national economy that result in 80-90% of its families not sharing in any of the income gains over a period measured in generations.

Skeptic

Skeptic

Ian Welsh presents at Firedoglake a chart very similar to the first one in my lead post.

He follows it with some other charts and a narrative of why this happened: oil and class warfare.

He follows it with some other charts and a narrative of why this happened: oil and class warfare.

Skeptic

Skeptic

Lane Kenworthy has this graph that shows increasing income dispersion.

Skeptic

Skeptic

Here from Chad Stone at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is another graph with different segmentation of the population but showing the same striking divergence of haves from have-nots after 1973. Note that since 1999 real incomes have stagnated even at the 95th percentile.

Skeptic

Skeptic

NYT has a set of graphics comparing salaries plus benefits of state and local workers with private sector employees, including this one that shows both leveled off in about 1975.

Skeptic

Skeptic

Kenneth Thomas in his Middle Class Political Economist blog discusses the pros and cons of various measures of income--hourly or weekly, individual or family, average or median, non-supervisory only or all workers, etc. here. He also addresses the question whether BLS cost of living stats or some other measure is the best way to adjust nominal incomes over time to comparable real incomes. And, in a good point I've not seen elsewhere, he points out that if we include in employees' compensation their employers' increasing costs of paying for employee health care there is an important question whether employees received real benefits, i.e., real compensation increases, from those increasing costs. The whole piece is worth reading, as is his blog in general.

Skeptic

Skeptic

When median real wages are tracked separately by gender, we observe substantial and continuous gains by working women from 1970 to 2000 and stagnation since. For working men the stagnation began in 1973 and has fluctuated between about 40K and 46K since, being near its low point now. David Ruccio posts the following graph with commentary at Real-World Economics Review Blog.

BTW, the ongoing convergence of US wages with Chindian wages that began in the 21st Century should be expected to drive further stagnation and decline of real US wages for both genders.

Skeptic

Skeptic

John Cassidy, writing November 18, 2013 in The New Yorker, brings us this powerful image from Piketty and Saez.

Also available here. The real pre-tax incomes (includes realized capital gains) of the top 1% of Americans barely moved from 1930 to 1963, while the incomes of the bottom 99% increased by a factor of about 3.4 from 1930 to 1973. Then in an abrupt reversal of trend, the incomes of the bottom 99% stopped growing except for a little surge from 1993 to 2000, and the incomes of the top 1% got onto a steep and continuing upward trend starting in about 1980.

Also available here. The real pre-tax incomes (includes realized capital gains) of the top 1% of Americans barely moved from 1930 to 1963, while the incomes of the bottom 99% increased by a factor of about 3.4 from 1930 to 1973. Then in an abrupt reversal of trend, the incomes of the bottom 99% stopped growing except for a little surge from 1993 to 2000, and the incomes of the top 1% got onto a steep and continuing upward trend starting in about 1980.

I like this graph because it zeroes out any possible effect of inflation adjustments which changed over the years and some contend are still not realistic because they don't adequately account for hedonic and quality improvements. Even if the adjustments are flawed, they are equally flawed for the 99% and the 1%. The graph also shows that from 1973 to about 1995 essentially all of the income gains went to the top 1%, and any gains by the top 2-5% or the top 2-9% necessarily were offset by decreases lower on the ladder.

Skeptic

Skeptic

David Leonhardt at New York Times has an interactive graphic that shows year by year since 1980 income growth rates (vertical scale) shifted from favoring the lower income percentiles (horizontal scale) to strongly favoring the highest percentiles.

Regretably, the scales did not copy. Click through to the article for access to the original graph and a stunning interactive graphic that shows the curve changing slope year by year.

Regretably, the scales did not copy. Click through to the article for access to the original graph and a stunning interactive graphic that shows the curve changing slope year by year.

Skeptic

Skeptic

A recent study based on Social Security data found that inflation-adjusted "lifetime" incomes of American men varied considerably depending on which year they entered the workforce at age 25. Entry years 1957 through 1967 was a period of rising lifetime incomes for all income levels. After entry year 1967, lifetime incomes declined for all but the highest income percentiles. Meanwhile, lifetime incomes for women entering the labor market from 1957 to 1983, the study period, continued to rise. Graph here. The NBER study is here (pay wall), and an NYT article with a graph for men is here. "Lifetime" means prime working years, age 25 to age 55.

Perhaps it's just a coincidence, but the beneficiaries of the rising lifetime incomes were all "Depression Babies," born between 1932 and 1942.

Skeptic

Skeptic

Here, at Brookings, is an interesting breakdown of which income tiers in which birth cohorts have or have not surpased their parents earnings. It summarizes work of Raj Chetty et al. published in an NBER working paper December 2016. In general, the higher the parents earnings, the fewer children surpassed them. The Chetty paper has much more information, including breakdowns by state. Good graphics.

Tuesday, March 3, 2009 at 01:30PM

Tuesday, March 3, 2009 at 01:30PM The title comes from Tim Duy via Paul Krugman. It means the Fed and Treasury still think bad financial assets are underpriced by the market and are trying different subterfuges to prop up the prices by having taxpayers assume the downside risk. They (and others) think policy makers are delusional about this.

Monday, March 2, 2009 at 09:34AM

Monday, March 2, 2009 at 09:34AM Wired has an interesting article explaining some of the mathematical inner workings of The Formula That Killed Wall Street, the "Gaussian cupola function" invented by David X. Li and adopted throughout the financial industry. The article explains why the model used assumptions about mortgage default losses exclusively from a recent ten-year period when default rates were low: The model doesn't input mortgage loss rates at all—it inputs market prices (the wisdom of mobs again) of credit default swaps as surrogates for mortgage loss rates, and CDS trading did not have a long history.

The article discusses who knew what about the limitations and inherent covert risks of the model and who may not have understood but, as Skeptic also reported here, it's clear that the herd instinct overwhelmed reason anyway.

Bankers securitizing mortgages knew that their models were highly sensitive to house-price appreciation. If it ever turned negative on a national scale, a lot of bonds that had been rated triple-A, or risk-free, by copula-powered computer models would blow up. But no one was willing to stop the creation of CDOs, and the big investment banks happily kept on building more, drawing their correlation data from a period when real estate only went up.

"Everyone was pinning their hopes on house prices continuing to rise," says Kai Gilkes of the credit research firm CreditSights, who spent 10 years working at ratings agencies. "When they stopped rising, pretty much everyone was caught on the wrong side, because the sensitivity to house prices was huge. And there was just no getting around it. Why didn't rating agencies build in some cushion for this sensitivity to a house-price-depreciation scenario? Because if they had, they would have never rated a single mortgage-backed CDO."

The only way to keep the herd off dangerous ground, and out of our gardens, is strong regulatory fences.

Thanks to Christine for the heads up.

Monday, February 23, 2009 at 01:24PM

Monday, February 23, 2009 at 01:24PM This is encouraging. Paul Volker, former chairman of the Federal Reserve Board and current advisor to President Obama, seems to agree with me that there is not much about "financial innovation" that reliably benefits the real economy--or even the financial economy, as it turns out.

Given the extent of the damage, financial regulations must be improved and enhanced to prevent future debacles, although policy-makers must be cautious not disrupt things further while the turmoil is ongoing.

Volcker, a former chairman of the Federal Reserve famed for breaking the back of inflation in the early 1980s, mocked the argument that "financial innovation," a code word for risky securities, brought any great benefits to society. For most people, he said, the advent of the ATM machine was more crucial than any asset-backed bond.

"There is little correlation between sophistication of a banking system and productivity growth," he said.

Sunday, February 22, 2009 at 05:00PM

Sunday, February 22, 2009 at 05:00PM David Warsh has a good summary of some options being discussed.

How's the US banking crisis going to end? Nouriel Roubini, of New York University, has taken the lead in urging the Swedish solution, namely government receivership: take 'em over, clean 'em up and sell 'em back to the private sector, preferably in pieces. Others, including Chris Whalen, of Institutional Risk Manager, argue that bankruptcy, like Lehman Brothers, is the best procedure. Kill 'em all and let the Bankruptcy Court of the Southern District of New York sort 'em out.

Former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan and Sen. Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina went out of their way last week to signal to their fellow Republicans that government receivership must be an option. "You should not get hung up on a word [nationalization]," Lindsey told the Financial Times.

Meanwhile, Citibank and Bank of America are fighting tooth and nail to preserve their hegemony. Indeed, Citibank wants more taxpayer money.

How about this instead? Capitalize half a dozen start-up wholesale banks with government money – call them Hamilton, Jefferson, Franklin, Madison, Adams and Washington. Get them borrowing and lending freely, purchasing assets from legacy banks, and then, equally swiftly, sell them off – privatize them.

Click here to read the rest of his post.

Tuesday, February 17, 2009 at 10:23PM

Tuesday, February 17, 2009 at 10:23PM Jon Hilsenrath at the Wall Street Journal:

The Greenspan Doctrine – a view that modern, technologically advanced financial markets are best left to police themselves – has an increasingly vocal detractor. His name is Alan Greenspan.

As Fed chairman, Mr. Greenspan was a frequent opponent of market regulation. Sophisticated markets, he argued, had become increasingly adept at carving up risk themselves and dispersing it widely to investors and financial institutions best suited to manage it.

The retired chairman has had to revise his views. In comments at a New York Economic Club dinner late Tuesday, the retired Fed chairman steered clear of much self-reflection on his role in the credit boom. But he did take a new swipe at the market's self-correcting tendencies and bowed his head to a new period of increased regulation.

"All of the sophisticated mathematics and computer wizardry essentially rested on one central premise: that enlightened self interest of owners and managers of financial institutions would lead them to maintain a sufficient buffer against insolvency by actively monitoring and managing their firms' capital and risk positions," the Fed chairman said. The premise failed in the summer of 2007, he said, leaving him "deeply dismayed."

Self-regulation is still a first-line of defense, Mr. Greenspan said. But after the financial collapse of 2007 and 2008, "I see no alternative to a set of heightened federal regulatory rules of behavior for banks and other financial institutions." He said hoped it would come in the form of tougher capital requirements for banks.

Wednesday, February 11, 2009 at 11:02AM

Wednesday, February 11, 2009 at 11:02AM Financial journalist Anatole Koletsky compares the plight of mainstream economics to historic intellectual disruptions.

In my column last Thursday, I explained how academic economics has been discredited by recent events. It is now time for what historians of science call a “paradigm shift”. If we want to flatter economists, we could compare this revolution needed to the paradigm shift in physics in 1910 after Einstein discovered relativity and Planck launched quantum mechanics. More realistically, economics today is where astronomy was in the 16th century, when Copernicus and Galileo had proved the heliocentric model, but religious orthodoxy and academic vested interests fought ruthlessly to defend the principle that the sun must revolve around the Earth.

He describes the work of Benoit Mandelbrot, George Soros, and several "imperfect knowledge economists" as contradicting fundamental assumptions of the mainstreamers, who rejected or ignored the heterodox ideas that focus attention on the relative high risk of financial crises.

One reason why such fruitful insights have been ignored is the convention adopted by academic economists some 30 years ago that all serious ideas must be expressed in equations, not words. By this weird standard, the intellectual giants of the subject — Adam Smith, Ricardo, Keynes, Hayek — would not now be recognised as serious economists at all.

Tuesday, February 10, 2009 at 12:47PM

Tuesday, February 10, 2009 at 12:47PM A former economics teacher "Wonks Anonymous" does a mea culpa about trade theory:

I believe that there is a fundamental problem with the analysis of free trade that most economists - myself included during my teaching career - present.

When a country has a relative scarcity of labor - like the US today - there are two impacts from trade with a labor abundant world: We see a slight gain in national income and a large redistribution of income from labor to owners of capital.

When faced with this result of trade theory we, as economists, have regularly waved our hands and mumbled something about the "winners" paying off the "losers" out of the overall gains.

Except that we never seem to see the winners paying off the losers.

The problem is that the gain in income is small - it's been years but my best recollection is that the estimated gains from NAFTA did not exceed 1% of GDP. It is a classic example of a "Harberger triangle". At the same time the redistribution is relatively large.

The political motivation for free trade is all about the redistribution and, as economists, we simply enable this redistributionist movement with our arguments about "efficiency"

Tuesday, February 10, 2009 at 09:30AM

Tuesday, February 10, 2009 at 09:30AM Robert Reich says Congressional Republicans are playing politics with the economic crisis. Rush Limbaugh has said he wants the stimulus package and bank rescues to fail so Republicans can win the next election. Robert Reich:

Republicans don't want their fingerprints on the stimulus bill or the next bank bailout because they plan to make the midterm election of 2010 a national referendum on Barack Obama's handling of the economy. They know that by then the economy will still appear sufficiently weak that they can dub the entire Obama effort a failure -- even if the economy would have been far worse without it, even if the economy is beginning to turn around. They'll say "he wanted more government spending, and we said no, but we didn't have the votes. Elect us and we'll turn the economy around by cutting taxes and getting government out of the private sector."

Obama believes Republicans will eventually embrace bipartisanship. I hope he's right but I fear he's wrong. They want to take back Congress the way Newt Gingrich retook the House (and helped Republicans retake the Senate) in 1994 -- with hellfire and brimstone. Once in control of Congress, they'll be able to block Obama's big inititiaves on health care and the environment, stop any Supreme Court nominees, and set up their own candidate for the White House in 2012.

Sunday, February 8, 2009 at 03:35PM

Sunday, February 8, 2009 at 03:35PM Paul Krugman is very worried about the pending economic stimulus package—

Because what's coming out of the current deliberations is really, really inadequate. I've gone through the CBO numbers a bit more carefully; they're projecting a $2.9 trillion shortfall over the next three years. There's just no way $780 billion, much of it used unproductively, will do the job.

Stan Collender explains that neither the regular budget process nor a budget reconciliation bill is subject to filibuster in the Senate and that both are possible in the next few months. He goes on—

My guess is that the Obama administration sees this, sees that it will get credit for even the changed version of the stimulus that is likely to get enacted, understands the political importance of an early legislative victory and, therefore, has decided to take what it can get now and come back for more in other ways in the not too distant future.

And even if that wasn't the orginal strategy, it certainly makes sense now.

Friday, February 6, 2009 at 03:39PM

Friday, February 6, 2009 at 03:39PM George Soros lays out here his narrative of what caused the financial crisis, how it has been mismanaged (especially by not saving Lehman Bros.), and the toxic effects of credit default swaps and collateralized debt obligations. After reading the views of many economists, this is refreshingly practical. The nation and world would be well served if his analysis and advice were heeded at least as much as that of the economists. He says at the end of his piece that he "will next outline the policies that in my opinion the Obama administration ought to pursue, and then assess how the future may play out," but I haven't found that part yet.

To understand the linked article, it is helpful to know that Soros strongly disagrees with the core assumptions of most mainstream economists that prices, in the financial world as well as elsewhere, tend toward equilibrium and that one can safely ignore brief price excursions away from equilibrium. Soros, who has been very active (and very successful) trading in financial markets for decades, says that prices often do not tend toward equilibrium but are inclined to self-reinforcing extremes on the upside and the downside. In his theory of "reflexivity" he says these irrational price swings can affect the actual value of the thing being priced--as for example in a bear run when a bank's rapidly declining stock price may cause loss of confidence in its survival, leading to a real and objective weakening in its ability to operate profitably.

Friday, February 6, 2009 at 01:51PM

Friday, February 6, 2009 at 01:51PM Thirty-six Republican Senators and nobody else voted for an amendment to the economic stimulus bill to strike out the entire contents and substitute nothing but permanent tax reductions benefitting high income individuals and corporations. Republican Senators Snowe and Collins of Maine, Specter of Pennsylvania, and Voinovich of Ohio voted against the amendment, and Senator Gregg of New Hampshire did not vote.

This is the summary of the amendment from the office of Senator DeMint, who offered it:

1) Defuse the 2011 tax bomb: Stop tax increases set to hit the economy in 2011.

- Permanently repeal the alternative minimum tax once and for all;

- Permanently keep the capital gains and dividends taxes at 15 percent;

- Permanently kill the Death Tax for estates under $5 million, and cut the tax rate to 15 percent for those above;

- Permanently extend the $1,000-per-child tax credit;

- Permanently repeal the marriage tax penalty;

- Permanently simplify itemized deductions to include only home mortgage interest and charitable contributions.

2) Long term, broad based tax cuts for American families and businesses.

- Lower top marginal income rates – the one paid by most of the small businesses that create new jobs – from 35 percent to 25 percent.

- Simplify the tax code to include only two other brackets, 15 and 10 percent.

- Lower corporate tax rate as well, from 35 percent to 25 percent. The U.S. corporate tax rate is second highest among all industrialized nations, driving investment and jobs overseas. Lowering this key rate will unlock trillions of dollars to be invested in America instead of abroad.

- This is not only good economic policy, but a matter of fairness. No American family should be forced to pay the federal government more than 25 percent of the fruits of their hard labor.