I have framed the American Dream as the expectation that new generations should do better economically than their parents, and have lamented the fact that real incomes of lower and middle economic strata have been stagnant and declining for 36+ years. In other words, what I'm calling "class mobility" has essentially stopped for the lowest and middle classes, making that version of the American Dream a mere memory. Another version of the American Dream is that individuals can rise out of poverty and disadvantage, get a good education, establish useful relationships, work hard, and achieve abundant lives while leaving their parents and peers behind—like characters in Horatio Alger stories. There is a lot of writing about this "re-ranking mobility," including ways to measure and increase it—especially where it seems to be limited by past or present invidious discriminations. One such post is here. I write to point out that class immobility and re-ranking immobility are different problems and that improving one does not necessarily improve, and could adversely affect, the other.

Class mobility, re-ranking mobility, age-related mobility and relations among them

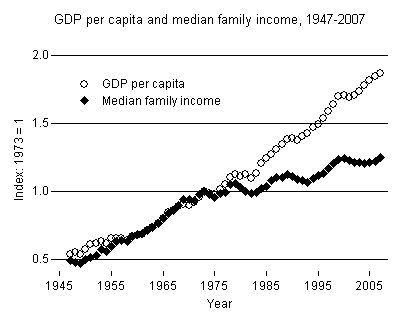

Class mobility is measured by taking an entire population, arranging them in rank order of income, and then dividing them into equal size groups, commonly 5 groups or quintiles. From the rankings one can derive the top and bottom incomes for each quintile, the average income of all persons in each quintile, and in US Census data demographic statistics like age, race, family status, and education. Incomes can be converted to "real" dollars to eliminate the effects of inflation. What I showed here is that average real incomes for the bottom 3 quintiles have increased only slightly or not at all between 1979 and 2003 and that progress of the second quintile was nothing to brag about. In contrast, from 1947 to 1973 there was a factual basis for the dream that all Americans would be better off than their parents at equivalent life stages: Real average incomes of the 5/6 of income earners who are non-supervisory workers (roughly but not exactly the bottom 4 quintiles) climbed steadily at a compound rate of more than 2% in that era. Post.

Now watch what happens to class mobility when our Horatio Alger hero uses re-ranking mobility to leap out of poverty in the bottom quintile and get into the middle quintile overnight. Nothing. The person who was at the bottom of that middle quintile is displaced to the fourth quintile, and the person who was at the bottom of the fourth quintile becomes the top of the bottom quintile. Because the number of persons in each quintile cannot change, simple arithmetic makes rank order mobility a zero-sum game.

It is also important to note that rank order of individuals can be confused by "age-related mobility," meaning the tendency for people's incomes to increase with age as they progress from entry-level jobs to peak earnings before typically declining with retirement or disability. That means that our hero may start in the bottom quintile with his parents, rise to the middle quintile in his most productive years, and fall into the fourth or bottom quintile in retirement years. We cannot usefully compare people's earnings at age 40 to the current earnings of their parents or to their own earnings at age 20, even if we adjust for inflation. Correcting for age-related mobility to measure how many people permanently migrate upward from the quintile of their parents can be challenging and uncertain, as described by "the buggy professor" in comments here.

But what if a million Horatio Alger heroes leapt from the bottom quintile to about the middle of the third quintile, wouldn't all three of the lowest quintiles have improved average incomes? After all, a million people just went from earning, say, $17,000 per year to, say, $40,000, for a total of $23 billion per year. Even if the number of people in each quintile must stay the same, the million people who lost rank will raise the averages in their new lower quintiles, and since our heroes landed near the middle of the third quintile, the average for that quintile will also increase. The answer is, "No," unless our heroes got one million new jobs created especially for them. If there are not that many new jobs waiting for them, then our heroes must have won the labor market competition for jobs that either were already filled, or were destined to be filled, by persons in the middle quintile, who were then displaced to lower income jobs or unemployment.

Actually, unless a million or so new third-quintile jobs are created for our heroes, the situation is worse than creating a false hope of $23 billion of additional labor income. The million new qualified applicants for those $40,000 per year jobs would competitively bid down the wages thereof to something lower, and those who lose out on those jobs would move down the ladder to jobs for which they may be overqualified and bid down those wages, etc. Thus, instead of increasing by $23 billion, total labor income would decrease by some amount due to a surplus of qualified workers competing for higher-skill jobs.

People who study re-ranking mobility tend to be concerned about the inequality of opportunity experienced by youth in socio-economic environments that are poorly correlated with economic success compared with youth who start out in upper quintile or non-minority families. Typically, studies that document such disparities propose costly ameliorative programs such as enhanced educational effectiveness and opportunities targeted at disadvantaged populations. That's fine. I'm for that. There is great moral and social-stability value in avoiding a permanent, self-perpetuating, alienated, underclass. Such social mobility programs will, hopefully, result in a "fairer" distribution of jobs, but do such programs create the millions of new jobs that are necessary to serve my primary interest, the restarting of long-term class mobility, i.e., steadily rising real incomes for all four of the bottom quintiles?

Rapid economic growth is necessary, but not sufficient, to raise labor incomes.

First, it seems, I have to address what economic forces tend to cause real incomes to increase in all quintiles. The answer is that the laws of supply and demand strongly apply in "labor markets." Anything that creates an oversupply of labor is advantageous to employers, which is presumably why employers consistently support tax expenditures to oversupply the labor market with the "public good" of "intellectual capital." Conversely, a labor shortage during the dot-com era (1997-2003) caused real median incomes to rise for the only time since 1979. Post. In my own experience, labor shortages and rising real wages occur only during periods of rapid growth and stagnate or decline when growth is slow. Adam Smith thought so too. From Wealth of Nations, bk. 1, ch. VIII:

When in any country the demand for those who live by wages; labourers, journeymen, servants of every kind, is continually increasing; when every year furnishes employment for a greater number than had been employed the year before, the workmen have no occasion to combine in order to raise their wages. The scarcity of hands occasions a competition among masters, who bid against one another, in order to get workmen, and thus voluntarily break through the natural combination of masters not to raise wages.

. . . .

The demand for those who live by wages, therefore, necessarily increases with the increase of the revenue and stock of every country, and cannot possibly increase without it. . . .

It is not the actual greatness of national wealth, but its continual increase, which occasions a rise in the wages of labour. It is not, accordingly, in the richest countries, but in the most thriving, or in those which are growing rich the fastest, that the wages of labour are highest. . . .

. . . .

Though the wealth of a country should be very great, yet if it has been long stationary, we must not expect to find the wages of labour very high in it. The funds destined for the payment of wages, the revenue and stock of its inhabitants, may be of the greatest extent; but if they have continued for several centuries of the same, or very nearly of the same extent, the number of labourers employed every year could easily supply, and even more than supply, the number wanted the following year. There could seldom be any scarcity of hands, nor could the masters be obliged to bid against one another in order to get them. The hands, on the contrary, would, in this case, naturally multiply beyond their employment. There would be a constant scarcity of employment, and the labourers would be obliged to bid against one another in order to get it. If in such a country the wages of labour had ever been more than sufficient to maintain the labourer, and to enable him to bring up a family, the competition of the labourers and the interest of the masters would soon reduce them to this lowest rate which is consistent with common humanity. . . .

In this passage Smith credits booming growth and a chronic labor shortage in the American colonies as causing higher real wages than in England. In contrast, he describes the low wages, unemployment, and widespread poverty in very wealthy but stagnant China, and the mass starvations in Bengal under the exploitation of The East India Company.

Although Smith said above, "The demand for those who live by wages, therefore, necessarily increases with the increase of revenue and stock of every country, and cannot possibly increase without it," that has turned out to be partially, and crucially, untrue. We have observed in recent decades that wages do not "necessarily" increase with growth. We have had "jobless recoveries" from the 1991-92 and 2001 recessions, and there seems to be a consensus of experts (Krugman, for example) that we should expect another jobless recovery from the current Great Recession. Furthermore, US job creation has been in a long secular downward trend since 2001, even through the recent housing boom, and has fallen way behind the population growth rate. (The NYT graph is here, and my discussion is here.) But the other half of Smith's sentence, that wages cannot increase without increases in national wealth does certainly seem to be still true. So, robust growth is necessary but not sufficient to support a rising wage level.

Why job growth has gotten disconnected from GDP growth and why it has become so much more difficult to create well-paying jobs and wage growth in America is beyond the scope of this post, but there is growing consensus that foreign labor demand arising out of globalization is a substantial cause.

How might increased re-ranking mobility create jobs and rising wages, or might wage levels be depressed instead?

First, to avoid confusion, I'll explicitly exclude one issue. Some argue that there will soon be robust job growth, especially for "knowledge workers," under business as usual conditions. For example, McKinsey Global here. For them, programs to increase re-ranking mobility are neither expected nor necessary to create millions of new jobs for college graduates. I think BAU conditions will not do that, that we already have a glut of college-educated labor, and that we need a demand-side strategy to create tens of millions of domestic jobs, as explained here, here, and here. But whether the optimists are right or I am, that has nothing to do with the question whether increasing re-ranking mobility will increase class mobility, as I will now explore.

In America, about 1.3 million youth leave school each year without graduating high school. Link. Consider what might happen if we implemented programs that drastically reduced that number of dropouts and increased by 0.5 million per year the number ready for college, compared to the 1.5 million who actually start college each year. The most plausible (IMHO) suggestion is that large numbers of jobs are created by just a few individuals having very rare combinations of innovative talent, entrepreneurial drive, and other skills, and that some of these rare individuals are in the group of 0.5 million presently being stifled by unfavorable socio-economic-educational circumstances. We can't identify them now, but if we can help this cohort break those bounds, the rare few will eventually emerge to perform at their full potential and create whole new industries. On the other hand creating 0.5 million additional college entrants each year could worsen the competitive situation that is already depressing earnings for college graduates. Which is the larger effect? Will there be enough future job creators in each 0.5 million cohort to employ all of them and more? Some might choose to believe that, but I don't think there is any supporting evidence.

Perhaps instead of expanding college enrollment, the additional 0.5 million high school graduates (who otherwise would have been dropouts) will just increase the amount of competition for a static number of college slots. Some of them will get to begin college careers, forcing others who under present circumstances would have gotten in to compete in the job market as high school graduates. Under this scenario, the average ability of entering freshmen should be higher, and the increased competition might make many more high school students work harder, further raising the average level of college readiness. Perhaps in this way, we could unblock the rare job creators without flooding the market for college graduates. Yet I don't see it working out that way. Employers want a surplus of college graduates. Groups who fought to free primary and secondary children from their stifling disadvantages will not want to see higher education denied their proteges, particularly when it's still true that college graduates have substantially higher lifetime earnings than high school graduates. And if there is a funded demand for higher education, colleges and universities will inevitably expand the supply. Probably there would be an expansion of enrollment, but less than 0.5 million per year.

Bottom line: An effective program to increase re-ranking mobility (typically by enhancing educational opportunities) would probably both unleash some stifled talent and bid down the wages of college graduates and cannot be relied on as a solution to the stagnant wage, class immobility problem. (Of course, if you're an employer, you probably think stagnant wages are a feature instead of a bug.)

Update on Friday, August 28, 2009 at 11:50AM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

Conor Clarke presents data here showing a strong correlation between family income and academic test scores and refuting Greg Mankiw's assertion that the difference is because smart parents have high incomes and dumb parents have low incomes and they pass on their intelligence genetically. If Mankiw is wrong and Clarke's authorities are right, then there is a possibility that rising incomes of whole classes of people might result in rising educational achievement by their children. So, while I argued in this post that improving educational achievement of disadvantaged children would not increase class mobililty, it is possible that causation works in the opposite direction.

Update on Thursday, October 22, 2009 at 10:19AM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

Ron Brownstein reviews here Creating an Opportunity Society, a new book by Brookings scholars Ron Haskins and Isabell Sawhill. They found that Americans believe that America is still the land of opportunity for reranking mobility, but that in recent decades the tendency for people to stay in the same income classes into which they were born is stronger in America than in Europe.

One tenet that separates the United States from other countries is our belief in upward mobility. A study of attitudes in 27 countries found that Americans, more than people elsewhere, tend to believe that intelligence, skill, and effort will be rewarded with success.

. . . .

More than 60 percent of Americans whose parents scaled the top fifth of the income ladder have reached the top two-fifths themselves, Haskins and Sawhill found. By contrast, 65 percent of Americans with parents from the lowest fifth of earners remain stuck in the bottom two-fifths. Though we venerate the American Dream, studies show that children born to low-income parents in the United States are more likely to remain trapped near the bottom than their counterparts in Europe, the authors report.

Update on Saturday, October 24, 2009 at 07:59AM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

The work of three OECD researchers suggests that Horatio Alger stories are more likely to occur in Denmark, Norway, Finland, Canada, and Australia than in the US, France, Italy, or Britain, according to Inside Story, an Australian publication.

Last month, after Barack Obama invoked the American Dream at Wakefield High School in Virginia, Inside Story looked at what the statistics show about social mobility in western countries. Although a family’s socioeconomic status invariably influences children’s prospects, the data revealed the influence to be large and inequitable in some countries. In France, Italy, Britain and the United States, family background plays a very significant role in determining adult income; in Denmark, Norway, Finland and Canada the effect is much smaller. Australia falls somewhere in between, closer to Denmark than to the United States. This puts the United States among a group of countries that are regarded as class-bound and stifling of individual initiative.

. . . .

[P]arents’ socioeconomic status obviously plays a vital role in school performance. Its influence is strong in the United States, France and Belgium and weaker in some Nordic countries and in Korea and Canada. Interestingly, it’s not necessarily only the child’s parents’ status that counts: “In over half of the OECD countries, including all the large continental European ones, students’ cognitive skills are more strongly influenced by the average socioeconomic status of parents of other students in the same school… than by their own parents’ socioeconomic status.”

The first link in the quotation is to the Economic Mobility Project of the Pew Charitable Trusts. The second is to an earlier Inside Story article. These writings may be a good way into further research about factors correlated with (and possibly influencing) reranking mobility.

Update on Monday, April 26, 2010 at 02:13PM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

This arresting chart showing dramatic declines in reranking mobility in the 1980s and 1990s is from this NYRB essay by Tony Judt based on his new book Ill Fares the Land.

The bars show the percentage of sons' incomes explained by their fathers' incomes. It seems likely that this has continued to rise since 2000 and may be approaching 50% in 2010, compared with 15% in 1950 declining to 11% in 1980, when the trend reversed and rose like a hockey stick.

Judt's essay also presents five other figures showing (i) how social immobility is correlated with income inequality across eight nations, (ii) the correlation of inequality and ill health across 19 nations, (iii) the correlation across 12 nations of inequality and mental illness, (iv) the correlation across 23 nations of inequality and homicide rates, and (v) the lack of any apparent correlation between health expenditures per person and life expectancy in 23 nations. Judt credits the figure to British epidemiologists Richard Wilkinson and Kay Pickett in their book The Spirit Level (2009). Professor Wilkinson has a slide show here in which he shows correlations between income inequality and many other adverse social phenomena.

Thursday, November 5, 2009 at 05:04PM

Thursday, November 5, 2009 at 05:04PM